Director Roger Donaldson returns home to make race-driver drama

Roger Donaldson is producing a feature based on car builder and champion race car driver Bruce McLaren.

FROM a sprawling CV that includes big-budget Hollywood affairs about cocktail barmen, bank heists, volcanoes, aliens and renegade spies, the director Roger Donaldson considers two films to have been the pivotal moments of his career. First comes Smash Palace (1981), because it represents his international breakthrough, and second, The World's Fastest Indian (2005), because of the enduring affection it engendered in audiences.

Both were made in New Zealand - unlike every other film Donaldson directed in between, and which kept him largely absent from his adopted homeland for the past 35 years. And both featured his other great passion, cars: Bruno Lawrence's enraged father in Smash Palace was a racing car driver; The World's Fastest Indian was the tale of record-breaking Kiwi motorcyclist Burt Munro.

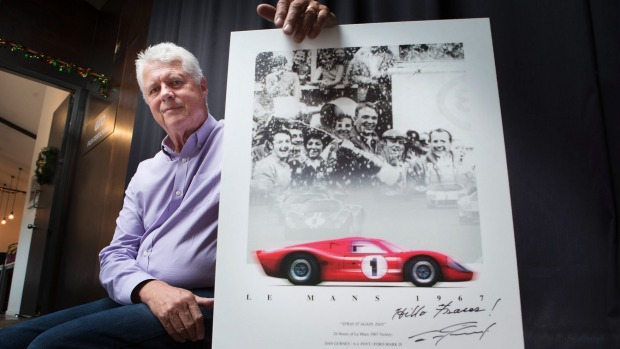

And it's a car movie that threatens to bring Donaldson, now 70 (but looking 50) back to New Zealand at least semi-permanently, three decades after he left what he once called a "barren landscape" for aspiring auteurs. December finds Donaldson parked happily in a small studio in Eden Terrace, central Auckland, editing a new documentary about the brief life of the Kiwi racing driver Bruce McLaren, who died behind the wheel at the age of just 32 in 1970.

"I know I will be back for a while," Donaldson says. "My family has come over and the kids are in school. I love New Zealand, and the only reason I am not in New Zealand is the reason I first left and went to the States for. And once I could make a living there making films, it was hard to come back and make a living here making commercials."

His love for New Zealand, he says, remains undimmed, but its a different place to the one he arrived in at 19, dodging the Vietnam War draft in his native Australia, and got started in still photography, commercials, and then in documentaries with Ed Hillary and Ian Mune, before he wrote and directed the 1977 thriller Sleeping Dogs, which provided the spark for the foundation of the New Zealand Film Commission. It was a lonely path back then, and carefully, he says, he might claim some credit for helping New Zealanders get their films sold internationally.

He and Mune did it first, selling their doco series Winners and Losers (1975) to 56 countries, starting with Sweden and ending with the US. The ignorance of youth helped, he admits. "It's hard to see yourself from the outside, but I think in my 20s and 30s I was a very dertemined person to make these films and I did whatever I could to convince people to get involved with them." He then took Smash Palace direct to American audiences to persuade them Kiwi cinema was worth watching. "Things are very different now," he says definitively, mentioning a film contest he'd judged to hand seed funding of $75,000 in which he would happily have funded every one of the finalists.

He hands much of the credit direct to Peter Jackson, and thus he's very dismissive of the criticisms of his contemporary, Goodbye Pork Pie director Geoff Murphy has of Jackson, that Jackson had somehow marginalised the Kiwi film industry by telling mainstream stories. ""It was completely unwarranted. I don't want to get into it but Geoff is talking through his arsehole. Peter Jackson is a great filmmaker and ... the fact he has made New Zealand the centre of his business is extraordinary. Geoff is an interesting character and he loves to say provocative stuff. Then he goes 'why does nobody want to back my movies?' when it's [because] you've told everyone they are a c---, so don't be surprised when they don't back your work."

Once Donaldson reached Hollywood, Donaldson amassed a CV of remarkably varied work, from movies like Cocktail and Species and Aliens to more heavyweight work like the Cuban missile crisis drama Thirteen Days and the Al Pacino-Colin Farrell spy drama The Recruit. The shared characteristic of them all, he believes, is focusing on his audience. "Movies is bums on seats. And that means entertainment. You can't make movies for yourself - you've got to make them for an audience. I never make the same one twice - if you compare Species and Thirteen Days, they are about as far apart as you can get, all they had in common was good actors ... but [with all of them] you want people to walk out of the theatre and say 'hey, I didn't waste my time or my money'... and to do that you've got to take them away from whatever they are escaping from."

While that varied CV contains almost every genre, including docu-dramas, the McLaren project is Donaldson's first pure documentary in nearly 40 years - and his last, an adventure around Cape Horn with Hillary, was never finished. "They're not easy," he says. "You've got to work hard to make a good documentary. [But] think re-enactment can only take you so far. It's Bruce, and we don't have the budget to do a clone of Bruce... this will be more compelling that any feature film could be, because Bruce is going to be Bruce in this story."

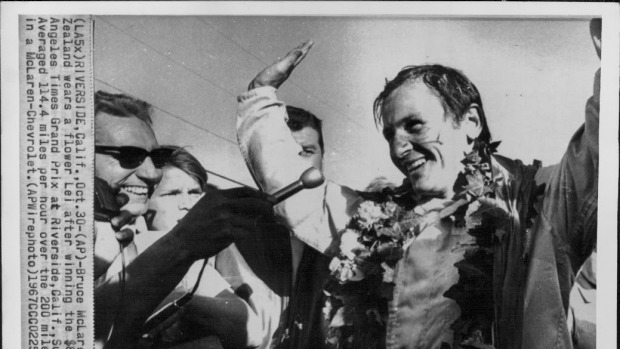

Donaldson begins reeling off the people he's spoken to - motor racing heroes like Chris Amon, with whom McLaren won the Le Mans 24 hour endurance race in 1966, Stirling Moss, Mario Andretti, Frank Williams and Jackie Stewart - and the people close to Bruce, like his best friend, the late Phil Kerr, and his mechanics Wal Wilmott and Howden Ganley. There's a story to be told, he thinks, in the people who knew Bruce, and how even 45 years after McLaren's death, somebody like Stirling Moss still remembers him with such passion.

But to make it really work as a documentary, he needs lots of Bruce: a difficult challenge from an era where very little was preserved in moving images. He's hoping our readers can assist, and ransack their garden sheds for forgotten memorabilia.

It's a tale worth telling, he says, even if many people won't remember Bruce McLaren, and it's the fact that Bruce's name lives on, in the famous Formula One car company, that makes it a viable tale. "There aren't too many Bruce McLarens out there - he is an icon of the automotive industry, and anyone who is a fan of cars and Formula One racing - but if you went out on the street, I think probably only one in ten people would know who he is. But if you said the McLaren car company, that he's a Kiwi, and that logo on the side of the car is a flying Kiwi, I don't know how many would know that."

The very fact of Bruce's early death is unremarkable in an age where car drivers had a ridiculously dangerous occupation. Donaldson recounts visiting Jackie Stewart's country estate and observing 50-odd garden benches dotted around, each inscribed with the name of a contemporary who had died prematurely in competition. He mentions McLaren winning a race, and thus a series, against Brabham, the day after teammate Timmy Mayer was killed in practice; he has footage of an TV interview McLaren gave the day after the death of Jim Clark where "you can see this resolve that, you know, this could never happen to you". His family, too, were probably inured to it: they had watched one race where McLaren was driving a red car, number 46, and another driver, in a red car number 64, flipped and died; it took them a while to realise it wasn't him. McLaren, indeed, wrote in his 1964 book From the Cockpit that "to do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy".

More, he thinks, it's what he achieved as a pioneering Kiwi driver in Europe, as a car designer and manufacturer in such a short time that makes him special. "For me, he's like Buddy Holly or James Dean: cut down in the prime of his life at 32, but he had still done a hell of a lot and left his mark. Not many people do that."

Donaldson knows the details in the way only an enthusiast could. He can still remember - and has it noted in his diary - as a child going with his car-crazy dad to see McLaren race at Sandown Park in Melbourne. "It's why I am still making movies about bloody motorcars," he says.

There's a neat circularity, though, that he had forgotten until the late Phil Kerr reminded him of it: one of McLaren's own cars actually featured in Smash Palace. Kerr organised the loan of a car Bruce had himself built, and it was Bruce's father Les who handed the vehicle over to Donaldson. In the movie, it's role is in in a framed photo in the lounge room of protagonist Bruno Lawrence's home in Horopito, Lawrence leaning on the bonnet.

The McLaren documentary's genesis came via an idea from producer Matthew Metcalfe (Love Birds, Dean Spanley), with an original treatment by screenwriter Glen Standring (The Dead Lands), while another actor-producer, Fraser Brown, enlisted Donaldson. The Giltrap car-dealership family are providing some of the financial backing. "They tapped the right guy," says Donaldson.

Actually, he says, he gets offered a lot of car movies: a group of German investors have seduced him with the idea of a movie about the Mercedes car company in the 1930s and it's involvement with Nazism, and he's also intrigued by an approach from US racing driver Danny Thompson to make a movie about his father, murdered land-speed world record holder Mickey Thompson.

But after the McLaren story, there are a couple of projects here that could keep him here for so much longer. He's interested in an idea about a movie about the pioneering New Zealand World War Two plastic surgeon Archie McIndoe. "I could be back here forever, if things keep happening. Movies take you all over the world, and the world is a small place now. But having a real reason to be in New Zealand, apart from that I have family here, and a vineyard here and friends here and I come here whether I am making movies or not, but it is good to have another reason, a work reason, to come here."

Help Roger Donaldson make his new movie

Roger Donaldson would love to hear from anyone with any of the following stashed away in their garden shed:

- shots or footage of Bruce winning races; Bruce's wedding; kids' drawings of racing cars from the 1960s; the Muriwai Beach races and New Zealand hill climbing races of the 1950s; the Tasman Series; footage or photos of Bruce at Seddon Tech; the Wilson Home, 1948-49, any personal photos or footage, including of a Bradshaw Frame (the medical equipment Bruce used for his leg); the memorial service for Bruce at St Paul's, London, 1970; a meeting of race car drivers shortly after at the Dorchester Hotel to discuss safety; video of Bruce's widow Patty accepting the Seagrave Trophy; footage or photos of Bruce in the CanAm races particularly CanAm Texas, his final race; New Zealand footage of Bruce's funeral; any overseas material, particularly of Bruce at places such as Pebble Beach, California; any personal material about Bruce, especially related to the family garage at Remuera Rd, or Bruce with his friends Phil Kerr or Colin Beanland; the Driver to Europe dinner where Bruce won his overseas scholarship.

Anyone who can help should email phoebe@generalfilm.co.nz.

Bruce McLaren (1937-1970)

Bruce McLaren was born in Auckland, to parents who owned a garage in Remuera Road, and father Les' passion for racing was soon inherited by his son. It was Bruce's performance in the 1958 New Zealand Grand Prix that drew the attention of McLaren's first mentor, the Australian driver Jack Brabham. McLaren won a European driving scholarship and began driving Formula Two cars. He won the 1959 US Grand Prix at the age of 22 years, 104 days, setting a new record for the youngest-ever driver and was runner-up in the 1960 season. He then founded the famous McLaren Formula One racing team, which continues to race today. McLaren died at the age of 32 when he crashed during testing at the Goodwood race track in England on June 2, 1970.

- Sunday Star Times